Black Muslims in America before Malcolm X

The presence of Black Muslims in America is popular opinion is inextricably linked to the Nation of Islam and Malcolm X; however Michael Gomez’s book ‘Black Crescent’ corrects that presumption and details the long history of Islam in the Americas.

Muslims in the Americas had not only come from Africa with the slave trade; it is believed 30% of Black African slaves were Muslim. It’s probable that many of them were also practising Sufis. However, not only did they come with the slave trade, but also with Columbus’s crew from Spain which was under Muslim rule for hundreds of years.

Moors (Muslims with Arab, Berber, Andalucian and West African heritage) had been in the Americas as both enslaved and free persons – but they were also there as those who had been convicted of crimes in Spain and elsewhere.

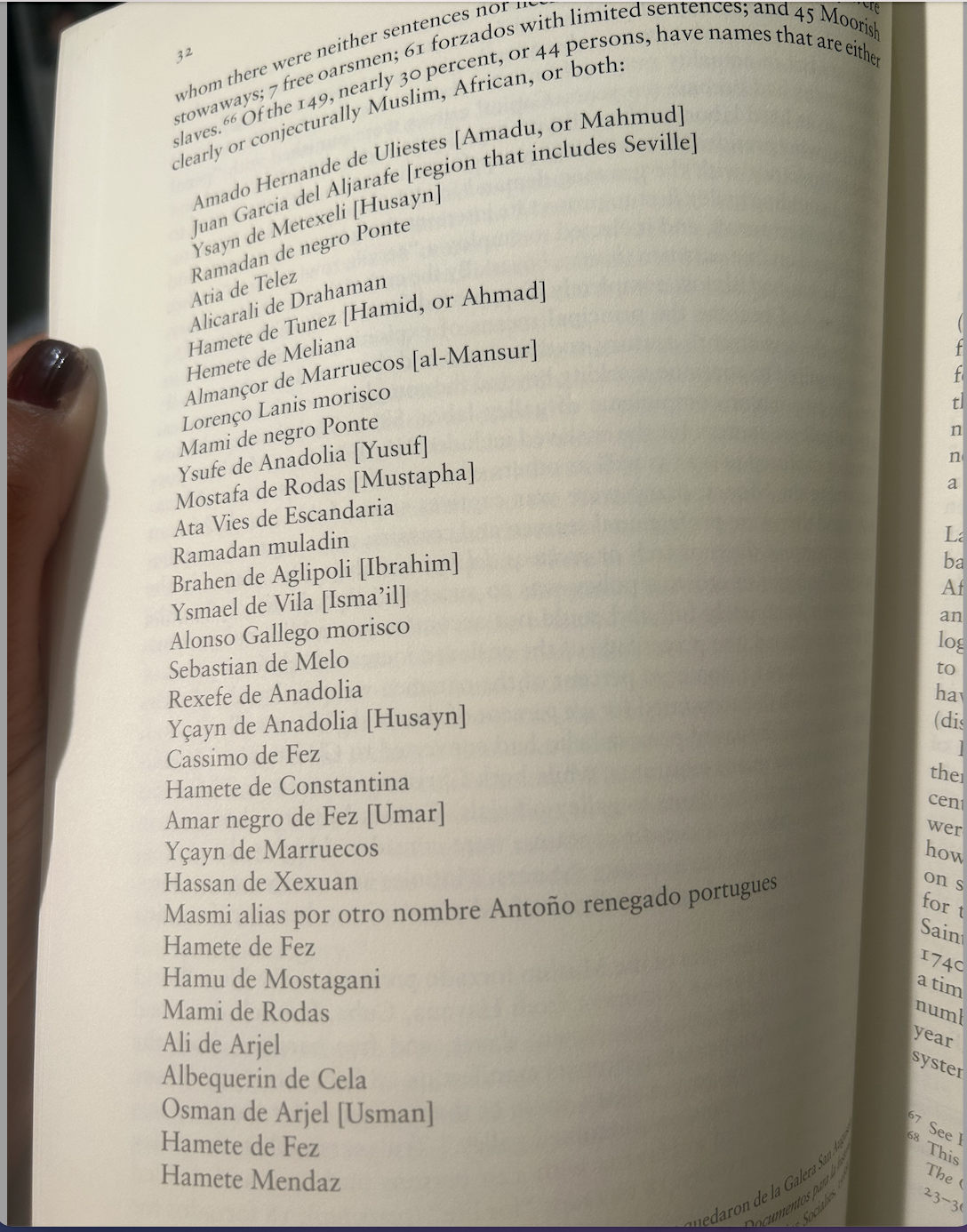

A document found in 1595-96 from Havana, Cuba has a list of those ‘criminals that were on a ship that arrived in Havana with 149 persons on board. Almost 30% of those names are ‘clearly or conjecturally Muslim’, says Gomez.

Gomez says in the opening of the book: “In 1492, Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic, and with him came Islam. Among his crews were Muslims who had been forced to profess the Christian faith; it is highly probable that Islam remained embedded in their souls.”

Islam would not have been alien to the slave traders, colonialists and other non-Muslim Africans who were enslaved, as many would have likely been very familiar with Muslims either through interactions in Africa, or via Spain which was still largely influenced by Muslim rule and through trade. The Spanish Christians were trying to purge Islam in Andalusia via the inquisition, and obviously did not want was this religion to travel to the Americas. Gomez says: “The last thing the Spanish wanted was for the New World to evolve into another theater of war in their protracted and costly struggle with Islam.”

Gomez says: “The Portuguese and Spanish became well acquainted with Muslims, a diverse assembly of differentiated unequals that included Arabs, Berbers, Arabo-Berbers, and West Africans. Together, they comprised the unwieldy and heterogeneric category referred to as ‘Moors’ by Europeans. Spanish use of the term ‘Moor’ in the sixteenth century, therefore, was not necessarily a reference to race as it is currently understood. Indeed, Berbers and Arabs had such extensive “contact with Negroes” that they had “absorbed a considerable amount of color.” Rather, ‘Moor’ referred to a casta (as opposed to nacion), a designation that “did not intend to imply a racial factor, but rather a cultural characteristic - Islam.“”

Gomez has quoted a variety of sources which show the large West African Muslim presence in the Americas from the time of Columbus. The Muslims who were enslaved largely came from Senegambia which was a majority Muslim land.

The other areas where slaves were mainly taken from as well as Senegambia included Sierra Leone, the Gold Coast and the Bight of Benin. “These four regions, in which Islam was of varying consequence, supplied approximately 53% of all those imported to North America.” These statistics lead Gomez to the conclusion that there were probably more Muslims taken as slaves to the Americas than is generally estimated. He adds: “This means that of the estimated 481,000 Africans imported into British North America during the slave trade, nearly 255,000 came from areas influenced by Islam.”

Jamaica was one of the Caribbean islands that had a Muslim presence from slavery. In 1789, 19% of Muslims in Jamaica would have been from areas such as the Gold Coast, Senegambia, Sierra Leone, and the Bight of Benin. “There was necessarily a community of Muslims in Jamaica who were aware of each other’s presence and who clearly enjoyed the advantages of close proximity and regular fellowship.” The most famous Muslim in Jamaica was known as Muhammad Kaba, born in 1756. He was from a wealthy family in Sengambia and was very well-educated. His name was changed to Robert Tuffit and even at 78 years-old he still said Islam had a special place in his heart.

Byran Edwards, a slave master, said that he could distinguish the Muslim slaves. ““Edwards was able to distinguish these Muslims not only (or even primarily) by their religion and bearing, but by their “complexions and persons” Referring to all African Muslims as “Mandingoes,” Edwards was particularly intrigued by “the tribe among them (called also the Phulies) (Fulani, or Fulbe) that seems to me to constitute the link between the Moors and Negroes properly so called.”” (as cited by Gomez).

Trinidad also had a Muslim presence. There is a statement from Reverend J.H.Hamilton, Rector, of the Church of England, who, after visiting Quare and Manzanilla, in 1841, said (as cited in Gomez): “Even the outward form of Christianity has almost disappeared amongst them; indeed, melancholy to relate, many of them have relapsed into the errors of Mahometanism, under the guidance of three Mandingo priests established amongst them. One of their number can write, and has copied portions of the Koran, which he reads to his assembled followers, and to whom they seem to look up with greatest reverence.”

Bahia revolt, Brazil

Although in Brazil Muslim presence was relatively smaller than in other parts of the Caribbean, it was the place which had one of the largest slave rebellions led by Muslims, the nineteenth century Bahia revolt. “It is, therefore striking that Muslims in Brazil, as will be demonstrated, would achieve a degree of renown entirely out of proportion to their actual numbers” says Gomez. He continues, “That a revolt occurred in Bahia in 1835, and that the revolt was led by Muslims, is established in the literature.”

Gomez states: “Insurrectionary activity had spread from the Hausa, suggesting that Islam was becoming an umbrella under which non-Hausa from the Bight of Benin found refuge, or with which they could identify to some degree, as not all who joined the rebellion were Muslims.”

After the revolt was suppressed, so was Islam and it started to disappear, at least at a public level. “Although it did not bring Islam to an end in Brazil, the suppression of the 1835 revolt was thoroughgoing. In addition to those condemned to death, prison, forced labour, and flogging, hundreds were deported from Bahia, some all the way back to West Africa.” states Gomez.

The Europeans had a long history with Islam. In the Muslim golden age, the Europeans were in awe of Islamic empires but at the same time hating and wanting to defeat them. The colonialists in America consequently wanted to eradicate Islam from the Americas. “The Spanish in Mexico (and elsewhere in Spanish-held territories) waged a deliberate and aggressive cultural war against Muslims in order to contain the spread of Islam,” says Gomez.

According to Sylviane A. Diouf in her book, ‘Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas’ African Muslims were known for their literacy levels. This literacy, along with the presumed privileged status of Islam among the Africans, was important in the history of slave revolts and efforts at resistance.

Muslims in New York

In New York, Gomez highlights that there is documentation of a few Muslims or potential Muslims in New York from the time of the Dutch East India Company. The area was then called new Netherlands. By time of English period, the evidence of Muslims in New York becomes a bit more indirect and speculative.

According to Gomez, there are still some indications of Muslim presence such as speculation is certain names reflecting a Muslim identity. For example, the name Sambo Sambo, which in the African Muslim language of Fulbe, Samba means ‘second son.’ That name was popular in the New York area.

Gomez highlights that some Muslim slaves would not only have come to New York from West Africa but some could have also come from Madagascar. Islam came to Madagascar from about the 12th century and there was Muslim presence on the island. Some of the ships coming from Madagascar had Muslim slaves that spoke about how people in their country could read and write Arabic.

Muslims in the South: Georgia and South Carolina

There was a significantly large numbers of Muslims possibly reaching into the thousands in the South of America. Here the Muslims tried to keep their faith going but in a private setting rather than more than visibly. Gomez argues that certain Christian worship practices developed by Black Americans was probably influence in some ways by Muslims.

The evidence for the presence of these Muslims in the South can be found from the Muslim names in slaveholder ledges, notices of runaway slaves with Muslim names in newspaper adverts and recordings of Muslim documents written in the Arabic script or language amongst other evidence.

The slaves with Muslim backgrounds were labelled as Mandingo or Mandinga. “The enslaved from Senegambia and Sierra Leone…often simply called “Mandingo” by whites, were generally viewed by slaveholders as preferable to others. Within the categories of Senegambia and Sierra Leone was the bulk of the Muslim imports, and as was true of Latin America, terms like Mandingo and Mandinga were equated with Muslims by the nineteenth century.” Although the Mande speakers were not all Muslim, the substantial percentage must have been.

There was a case study of a slave called Salih Bilali; it is assumed that he died in the late 1850s. An interview with 88-year-old Ben Sullivan, living in the same area of Saint Simons by The Works Progress Administration in the 1930s, shows that he was the grandson of Salih Bilali. The name of Ben’s father was Belali which indicates the grandfather wanted to pass on his Islamic identity. He was remembered by others for reading the Quran and praying like a Muslim would pray.

In a different case study was another man called Bilali or ‘Ben Ali’. He had a large family of 12 sons and seven daughters – an observer in 1901 said they worshipped Muhammed. A descendant, Katie Brown – who was the granddaughter of Margaret (one of the daughters) said that Bilali and his wife Phoebe would pray like Muslims. They said that they used beads and would say ‘Ameen’, and also that Margaret wore a head covering.

“Taken together, the testimonies…provide the essential contours of Muslim life in early Georgia – prayer mats, prayer beads, veiling, Qur’ans, dietary regulations, and daily, ritualized prayer. The composite picture is consistent with a serious pursuit of Islam” states Gomez.

“The Muslim presence in coastal Georgia-South Carolina (and possibly elsewhere along the Atlantic) was therefore active, vibrant, and compelling. Clearly, the history of Africans along this corridor is more complicated than previously understood; its study can no longer be limited to the Gullah language and associated handicrafts and artefacts, notwithstanding their importance” says Gomez.

However, it was hard and almost impossible to practice Islam due to slave owners and colonialists’ efforts to rid the slaves of their identity and heritage. Gomez states: “A campaign within the post-1830 militant South to use religion as a means of social control. As Africanized Christianity slowly became of force, Islam would have suffered.”

As a result Gomez says: “Many Muslims had little choice except to marry non-Muslims. Further, African-born Muslims may have been unable to effectively communicate with their children and grandchildren and would have been frustrated in their attempts to convey the tenets of Islam adequately.”

Although the connection to Islam was watered down, there was still elements of its practice and presence amongst the African Muslims and indeed other Africans who may have been influenced by aspects of Islam. “The gradual loss of Islamic knowledge, combined with the parochial application of Arabic to religious discourse, constituted a blow to the continuation of Islam in the early American South” states Gomez.

Noble Drew, Ali, and the foundations of contemporary Islam in African America.

Noble Drew Ali, born in 1886 in North Carolina was the bridge between Muslim legacies of the 18th and 19th century and Muslim communities of the 20th and 21st century.

He founded the Moorish Temple of Science which had aspects of Islamic teachings but was mixed with other practices as well. The teachings were contained in their ‘Circle Seven Koran.’

Gomez states: “His ideas (Noble Drew) reflect the quintessential convergence of Islam, Islamism, Freemasonry, New Thought, Rosicrucianism, anti-colonialism in its critique of European imperialism, and nationalism in the rejection of white American racism.”

“If the Muslim legacy extending from enslaved African Muslims was vibrant and undeniable by the 1930s, it was probably even more so during the 1880s and 1890s. That is, a scenario in which Noble Drew may have had some personal contact with Muslims or their descendants, or in which he had at least some familiarity with concepts associated with Islam”, says Gomez.

Noble Drew had a growing following (30,000), and his teachings around black pride and strength had not been his ideas alone as there were black leaders previously who had taught such concepts including Father George W. Hurley, born in 1884 in Georgia, and the Abyssinian movement which called for American blacks to repatriate to Africa and specifically, Ethiopia. Noble Drew thought highly of Marcus Garvey as well – but there is no evidence that Garvey reciprocated, or even knew who he was.

He said that African-Americans were Muslims who could trace their heritage to Morocco, and an even earlier Moabitic origin. Upon conversion to Moorish science, followers would take the surname Bey or El – these symbolised their free national names. This changing of the slave surname was something that the Nation of Islam would readily adopt.

The Moorish Temple of Science even adopted their own flag – a red Moorish pennant with a green, five-pointed star in the centre and wore a red fez hat.

Noble Drew said “We are returning the Church and Christianity back to the European Nations, as it was prepared by their forefathers for their earthly salvation. While we, the Moorish Americans are returning to Islam, which was founded by our forefathers for our earthly and divine salvation” as cited by Gomez.

He also expressed an abhorrence to marry anyone from ‘pale skin nations.’ Gomez states: “In addition to being a prophet, it would appear that Noble Drew Ali saw himself as the reincarnation of Jesus and Mohammed.”

The other popular form of Islam in late nineteenth century North America was the Ahmadiyya movement. Ghulam Ahmed of Punjab declared himself to be both the Mahdi and the promised Islamic Messiah in 1890. He espoused the concept of continuous prophecy – that the prophetic office did not end with the Prophet Muhammad’s death. He claimed to be a Prophet, just as Prophet Muhammad had been.

Ahmadiyyas promoted pan-Africanism and pan-Islamism. It was probably the most influential community in African-American Islam. It was dominated by Black Muslims in North America and was the most prominent form until the Nation of Islam. The Ahmadiyyas attracted a large number of jazz musicians of African descent.

In the 1940s to 1950s, there were many Black Muslims entering orthodox Islam “without an intervening phase of Moorish Science or the Nation of Islam” says Gomez. He adds: “However, their numbers were minuscule, testimony that most would indeed embrace the teachings of Noble Drew Ali or Elijah Mohammed before the seachange made possible by the career and personal example of Malcolm X.”

In the early 20th century, there were many groups with Nationalist, pan-Africanist, and uplift philosophies which were filtered through the idiom of religion. “Indeed, Noble, Drew, Ali was the first of a triad of prophets associated with Islam, followed by Ghulam Ahmed and Elijah Mohammed, and thus he paved the way of the acceptability of variance” states Gomez.

The main difference between Noble Drew Ali and the Nation was that the former wanted his followers to be peaceful and obey American laws. Elijah Muhammad was more radical. However, both had connections to Islam due to the historic presence of the religion in America. “Noble Drew Ali, as the foundation for Islam among African-Americans in the twentieth century, may very well be their link to an African Muslim past, as he was born and reared in an area contiguous with Melungeon and Ishmaelite influence at a time when the descendants of verifiable African Muslims may have yet been practising Islam along the Georgia and South Carolina coasts” states Gomez.

Gomez adds: “What motivated Noble Drew Ali to embrace his form of this religion? The answer is by no means as clear as the record of thousands of African Muslims who came to North America in chains, who struggled to maintain their faith against overwhelming odds, and who left their impressions, however imprecise, upon the sounds of human hearts and memories.”

The Nation of Islam

The Nation of Islam would go far beyond the limits of Moorish science. It was able to evolve in response to changing circumstances. “It is the Nation that, perhaps surprisingly, provided the multigenerational experience through which the transition from nonorthodoxy to orthodoxy was accomplished” says Gomez.

The original Nation’s leader, Fard Muhammad was half east Indian and half white. It is believed that he came to the USA from New Zealand.

He taught followers about healthy eating, which Elijah Muhammad continued to preach, and about using the Qur’an as opposed to Noble Drew’s Circle Seven Koran. He also claimed to be ‘God’ in person, which went far beyond the teachings of the Moorish Science Temple.

Elijah Muhammad took over from Fard Muhammad to lead the Nation. He was born in 1897 and always felt entitled and that he was born for a special purpose. Elijah Muhammad was convinced that the teachings of the church were hypocritical and erroneous. From a young age, he refused to become a member of the church.

Elijah Muhammad grew up in Georgia and South Carolina which was the historical epicentre of Muslim activity in the American South. He sought out Fard Mohamed and then converted to Islam. Fard had to suddenly flee because he was arrested on murder charges. That was the last time he saw Elijah Mohammed. The latter then assumed leadership and moved the Nation’s headquarters to Chicago.

The Nation was rebuilt by Elijah Muhammad. He became rich, and stressed economic independence and self-reliance for the black community as did Garvey. This concept of the white man as a ‘devil’ was not new and Elijah Muhammad was not the first Black leader to equate the white man with ‘evil’ and ‘satan’.

This idea of whites as devil or evil is not new. It was an important discursive tradition within the black community. “The very nature of whites was a subject of extended conversation and speculation, and, for not a few, it was the determination that something was amiss, so much so that it was in fact evil,” according to Gomez. He continues, “In other words, there were many in the black community who referred to whites as devils, long before Elijah Muhammad and probably antedating David Walker.”

Elijah Muhammad was critical of Christianity and whiteness. He said “they (the so-called Negroes) hang the pictures of white people on the walls of their homes… “They (the so-called Negroes) go to church and bow down to the statues under the names of Jesus and Mary, and some under the name of Jesus‘s disciples, which, again, are only the images of the white race, their arch deceivers” as cited by Gomez.

He believed that white people were duplicitous. In his view, their deception began with religion and branched out to other areas. He said: “They came as traders in commodities, but they departed as traffickers in human beings. They were not what they seemed, so said traditions circulating throughout the South” as cited by Gomez.

In regards to the role of women within the Nation, Elijah Muhammad taught that men were supposed to be protectors and guardians of women. He preached that women should protect themselves from immorality, stop bleaching their skin, going out to bars and similar behaviours to white people. The women who came to the Nation of Islam were in fact attracted to the treatment of women by Muslim men as they felt respected and classy.

An off-shoot of the Nation was the ‘Five Per Cent Nation’ who moved away from the Nation of Islam in 1964. The founder Clarence 13X did not agree with all of Elijah Mohammed’s philosophy. His message was internalised by leading artist of rap music and hip-hop culture such as Nas, Rakim and the Wu-Tang Clan.

The teachings of the Five Per Cent Nation believed that only five per cent of humans were righteous and understand the truth. This according to them was that the living God is the black man who empowers black communities. It was also known as the Nation of Gods and Earths, where black men are Gods and black women are queens.

Malcolm X

Malcolm X‘s parents with Garveyites and believed in pan-Africanism. His father was a minister and spoke out against slavery and the treatment of black people. He was killed in 1931 in what was most likely a racist murder.

Malcolm’s mother taught him to not eat the swine and rabbit, and when he first encountered the Nation and was told not to eat pork, he remembered his mum also teaching him the same thing.

Malcolm X did get into trouble with the law, but when he was in prison and found the Nation of Islam, he reformed his life and became a very disciplined, pious and principled person. Gomez says: “Malcolm was not the stereotypical opportunistic leader, and from all indications he was resistant to corruption.”

Malcolm X was a strong advocate of pan-Africanism right until the very end of his life, even when he converted to orthodox Islam. This connection with Africa was strengthened when he visited many lands on the continent, and these trips helped to move Malcom X further away from Elijah Muhammad. He spent five months travelling across Africa. Gomez states: “His commitment to pan-Africanism reinvigorated, Malcolm would have also noticed in his overseas travels significant differences between Islam in the Muslim world and its practice in the Nation.” Ironically, Elijah Muhammad after visiting Africa felt “repulsed” by the continent.

When JFK was assassinated, the press interviewed Malcom X asking for his response to the murder. Malcolm spoke his mind, and being critical of America’s foreign policy and imperialism said that the assassination was the result of “chickens coming home to roost”. Elijah Muhammad was furious that Malcolm spoke out of turn, and he banned him from public appearances for 90 days.

Some say that the JFK incident was an excuse to get rid of Malcolm X because there was growing jealousy towards him in the Nation and eventually from Elijah Muhammad. Gomez states: “It is irrefutable that Malcolm’s ministry was the primary reason for the Nation’s rapid rise in the seven years between 1957 and 1964.” However, sadly his success and brilliance led to his downfall within the Nation.

Malcolm X went to Hajj in April and May 1964 after leaving the Nation, and he embraced orthodox Islam and wanted to be know as El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. He was still committed to pan-Africanism and his aim was to bring America to justice for human rights abuses against Black people in America.

Malcolm X was assassinated on 21 February at the age of 39, but left a huge legacy in the fight for freedom for African Americans. Malcolm was a great man and respected leader, and his story is the not the beginning of Islam in America but the result of a long legacy of Islam in America. Gomez states: “In becoming his own original man, Malcolm was connecting to his ancestral origins.”